Listed as threatened since 1977

Now more than ever, the southern sea otter depends on The Otter Project’s advocacy for enhanced species’ protections due to increased burdens facing the already threatened species.

A lack of quality habitat, threat of catastrophic oil spill, and poor water quality threaten the recovery of the keystone species.

The principal threat facing the sea otter is an oil spill from a large vessel transiting the California coast. The threat is only exacerbated by a historically slow pace of natural range expansion. Key to the recovery of sea otters is an increased range to combat current resource limitation. The otter’s range remains restricted due in part to a historically imposed “no-otter” management zone. Established in 1986 as part of an effort to translocate sea otters to San Nicolas Island, the zone was created in response to the fishing community’s concerns of commerce interference. However, as a transitory species, otters’ movements cannot be contained, and ultimately it was determined that the no-otter-zone inhibited the species’ recovery.

Today, the sea otter’s range is restricted by severe kelp losses leading to a lack of kelp canopy. The kelp die-offs also generate high risk areas for sea otters without refuge from sharks. Increasingly, shark bites are resulting in sea otter mortalities.

Destructive climate change impacts also threaten sea otters. These impacts include harmful algal blooms, ocean acidification, and habitat loss (including severe kelp die-off), as well as diseases and anthropogenically generated contaminants. Harmful algal blooms, biotoxins, and rising levels of ocean acidification and temperatures, are becoming more prevalent. 2021 research shows algal toxins produced by harmful algal blooms are slowly destroying southern sea otters’ hearts.

Status Report

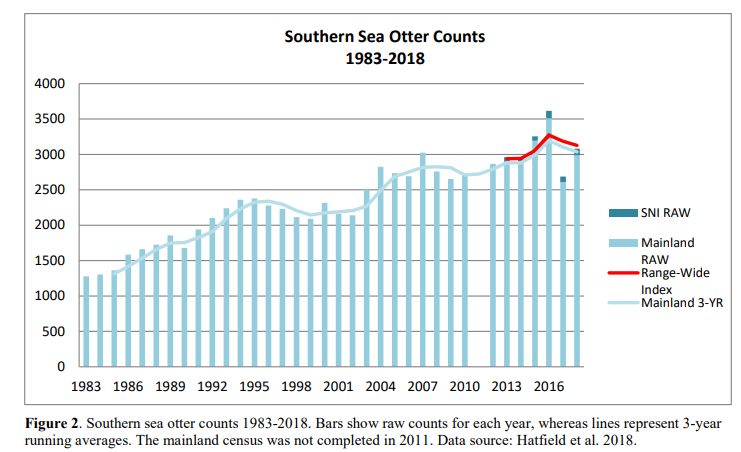

A 2019 USGS Census determined that the 3-year average of combined sea otter counts from mainland range and San Nicolas Island was down to 2,962, a decrease of 166 sea otters from 2018, and a population level signifying both a continuously threatened and depleted stock.

According to USGS, the negligible trend in sea otter counts “corresponded to the lack of meaningful population range expansion.” The USGS 2019 survey found the sea otters’ population to be largest between Seaside and Cayucos. The area of greatest southern sea otter population density is the Monterey Peninsula.

Unsustainable Prey Availability

Despite population growth from 2010 to 2018, there was a marked decline in southern sea otter population in 2017 and 2018. USFWS found the population growth from 2010-2018 was the result of sharp increases in sea otters in 2015 and 2016 in response to an unusually high abundance of prey. Smith et al. found the combination of star wasting disease and a 2014 El Niño event let to a temporary growth in purple sea urchin and an increase in sea otter survivorship on account of an increase in sea otters specializing on urchin prey. The very purpose of the 2003 Sea Otter Recovery Plan’s usage of a 3-year running average is to avoid the impact of anomalous years on the Sea Otter’s recovery. However, the combined El Niño and star wasting disease produced a “blob” event of purple sea urchin, creating unsustainably available prey for the southern sea otters. It is therefore important to be aware that the population growth yields seen in 2015 and 2016 have not since continued.

Target sustainable

population

Southern sea otters historically ranged throughout the California coast but were hunted to near extinction by the early 1900’s. Protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1977, the sea otter population began to grow but was isolated to the central California Coast. Under the ESA and Marine Mammal Protection Act, Federal agencies are charged with managing sea otters to their optimum sustainable population level. An optimum sustainable population refers to “the number of animals which will result in the maximum productivity of the population or the species, keeping in mind the carrying capacity of the habitat and the health of the ecosystem of which they form a consistent element.” The 2003 Sea Otter Recovery Plan determined optimum sustainable population to be approximately 8,400 sea otters. However, this number is the lower bound of the optimal sustainable population level for the entire California coast based on estimated historic population levels and represents roughly 50-60% of the habitat’s current carrying capacity. More recently, in January 2021, Tinker et al. produced a report in The Journal of Wildlife Management finding that 1) California could eventually support 17,226 otters, and 2) when projecting a 59.4% carrying capacity, the optimal sustainable population for all of California and for regions within California is 10,236 sea otters. The significance of these findings is a possible increase in what was previously considered as the target “recovery” for the southern sea otter.